White males make up the largest sector of the U.S. workforce and have, on average, always made the highest salaries. If we compare their salaries to those of women, ethnic minorities, the differently-abled, and LGBTQ+ persons, we see a large disparity between the wages of similarly-qualified candidates in the same fields.

The gap is glaring, and unfortunately, eliminating it isn’t as simple as raising salaries for other employees. It requires attention to differences in education, experience, and seniority, even though we know such factors are affected by the same biases that determine salary.

To complicate matters, agreeing on how to measure the wage gap with so many variables is murky at best. For example, a Pew Research Center analysis of median hourly earnings of both full and part-time workers in the United States found that women earned 85% of what men earned – a 15% wage gap. By comparison, the Census Bureau in 2017 found that full-time, year-round working women made just 80% of their male counterparts – a 20% wage gap. The AAUW’s 2019 updated wage report found a 35% difference between the salaries of the average woman ($45,097) and man ($55,291) in America. PayScale’s 2020 survey women make only $0.81 for every dollar a man makes.

Our cultural expectations of women as caregivers throw another wrench into the calculations, especially in light of the COVID pandemic. While a 2018 study by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) showed that women faced an actual wage gap of 51% between 2001-2015, those who took just one year off from work had annual earnings 39% lower than those of women who remained in the workforce. Their updated 2020 study “Build(ing) the Future: Bold Policies for a Gender-Equitable Recovery” revealed that women have also experienced a disproportionate number of job losses since the start of the pandemic. From February to May 2020, 11.5 million women lost their jobs, compared with 9 million men.

But it’s also important to note that 4 times as many women aren’t currently looking for work compared to men. In the words of the IWPR, we are experiencing a “shecession” that has seen 865,000 women drop out of the labor market altogether between August and September 2020. That’s because family care responsibilities fall predominantly to women. Homeschooling as well as child and elder care are making it impossible for women to reenter the workforce at the same rate.

Who gets paid the most (and least)?

Data from Hired’s 2019 survey highlight the inequality between men and women:

- 60% of men are offered 3-4% more for the same role as women at the same company, which is technically illegal in the U.S.

- 41% of the time, companies interview only men for an open position.

- 61% of the time, women are asking for lower salaries than men (this was true in all fields).

Data from AAUW’s 2019 report suggests even more gender wage disparity when we break the statistics down by race. On average, for every dollar made by white men…[su_pullquote align=”right”]…it’s also important to note that 4 times as many women aren’t currently looking for work compared to men. In the words of the IWPR, we are experiencing a “shecession” that has seen 865,000 women drop out of the labor market altogether between August and September 2020.[/su_pullquote]

- Black women made 62 cents

- Hispanic women made 54 cents

- Asian women made 89 cents

- Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander women made 61 cents

- American Indian or Alaska Native women made 57 cents

In addition, the pay gap increases throughout a woman’s career and is widest for women ages 55-64.

These numbers show general trends but differ year-to-year by survey, industry, location, and education levels. A lack of reporting from some groups and career sectors also hinders precise measurements. Nevertheless, dozens of studies and surveys have corroborated evidence of a gap between white men and other groups in all fields of employment.

The power of transparency

One of the biggest problems in assessing the wage gap is getting accurate salary data. Studies have shown that most employees are uncomfortable sharing salary information, and even go to great lengths to conceal their pay from coworkers. At times, Employers actively discourage sharing salary information.

But there’s a small group of people leading the charge to be more transparent. Employees from many sectors have made efforts to share wage data online so it can be accessed and assessed. These websites and spreadsheets often don’t ask for names, but rather positions, education, experience, location, salaries, and other benefits. Of course, the problem, even for well-known salary comparison sites like Glassdoor, is that the information is crowd-sourced and unverified. But while there’s always the possibility for dishonesty, it’s given many employees a good reference point for negotiations.

Knowing where you stand in the wage hierarchy also affects morale. Seeing how much (or little) someone else makes can lead to anger and resentment until the problem is solved. Employees need more tools for asking about equal pay at work, and employers owe it to them to explain discrepancies to reduce wage gaps that exist because of pure bias.

Who is underpaid?

Women

It has been illegal for companies to pay women less for the same job as men for over half a century in America. Nevertheless, it happens all the time – sometimes without companies even realizing it because they don’t keep those sorts of statistics. But with the now constant calls for equal pay and increased diversity, employers can no longer afford not to identify and improve salary inequalities.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]The vast majority of non-white workers are paid less than their white counterparts. And the disparity is always the largest for minority women. [/su_pullquote]Plain, old-fashioned bias is likely the main reason that women are paid less than men, even for the same job. We tend to devalue what we consider to be “women’s work”, resulting in occupational segregation, where even skilled jobs typically held by women tend to come with lower wages. And because women have internalized a lower “worth” in terms of salary, they commonly ask for less than men when negotiating their compensation packages. Without knowing what colleagues make, most women are flying blind when it comes to salary negotiations.

Women are also disadvantaged in the workplace because domestic duties – from bearing and raising children to eldercare – often fall to them, necessitating time off from work. This is also why women tend to be overrepresented in part-time work, which is often paid hourly and at a lower rate than full-time work.

It’s crucial to remember that wage inequality isn’t just an issue for the underpaid, however. It affects the entire economy and, therefore, all of us. Women are the sole or co-breadwinners in two-thirds of American households, so their wages affect the well-being and need for social services of other dependants.

On average, here is how much women of different ethnicities earn for every dollar earned by white men:

To top it off, the pay gap increases with age. And no matter how long a woman has been working, she may have a good chance of facing an income gap in retirement as well. Anyone who has earned less over their working years will have lower Social Security payments. The AAUW report also found that women lag behind men in pension benefits and every source of retirement income.

Ethnic minorities

The vast majority of non-white workers are paid less than their white counterparts. And the disparity is always the largest for minority women.

Data from Pew Research in 2016 showed that white and Asian women have narrowed the wage gap with white men to a much greater degree than black and Hispanic women (though this is a hard population to get a handle on because of its diversity). White women narrowed the wage gap in median hourly earnings by 22 cents from 1980 to 2015; black women by 9 cents; Hispanic women by just 5 cents. Asian-American and Pacific Islander women narrowed the gap by 27 cents.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]While it’s easy to suggest that education is the reason for this disparity, the evidence does not support such a theory. College-educated black and Hispanic men (as well as white and Asian college-educated women) still earn roughly 80% of what their white college-educated colleagues earn.[/su_pullquote]Pew’s research showed that black and Hispanic men made almost no progress in narrowing the wage gap with white men since 1980. As of 2015, black men still earned just 73% of white men’s hourly earnings, while Hispanic men earned 69% (down from 71% in 1980).

While it’s easy to suggest that education is the reason for this disparity, the evidence does not support such a theory. College-educated black and Hispanic men (as well as white and Asian college-educated women) still earn roughly 80% of what their white college-educated colleagues earn. Black and Hispanic women earn less than 70% of what similarly educated white men are paid.

In fact, a 2020 update from the AAUW found that Black women with a high school degree earned 65.99% of what similarly educated white men earned. But when they completed a bachelor’s degree, their earnings actually dropped to 65.14% of what white men made. The same was true for Latinas, whose earnings went from 66.78% to 62.73% after graduating with a bachelor’s. Native American women’s numbers went from 66.7% to 59.2% after getting a higher degree.

Even when we control for education – since the number of black and Hispanic college-educated workers is lower – they still make less money than whites.

The differently-abled

According to the U.S. Census, the U.S. has roughly 9 million workers that identify as disabled (and likely many more since invisible disabilities are underreported).

[su_pullquote align=”left”]…this wage gap has some serious consequences for the American economy. They estimate that if workers with disabilities received the same pay as their colleagues, they would add $141 billion to the economy (or 1% of the GDP).[/su_pullquote]In the early years of someone’s career, those with the most commonly-reported disabilities (ambulatory, hearing, and cognitive) tend to concentrate in certain sectors. Census data shows that median earnings are “about the same” as those without ($.87 on the dollar). However, these workers are less likely to work full-time or year-round.

The American Institute for Research (AIR) has shown that people with disabilities earn on average 37% less than non-disabled people, and the pay gap actually increases with higher education levels.

More recent Census data found that among the 11 million employed Americans with disabilities, their median earnings were just 66% of that of their non-disabled peers. The Brookings Institute found that as of 2018, disabled people with a high school degree had a 10% lower employment rate than non-disabled people. Among disabled college graduates, the employment rate was 27% lower. AIR reported that the annual disability pay gap among workers with Master’s degrees was over $20,000 per year.

There’s plenty of doubt about whether these numbers will change in the near future. Harvard Business Review reports that while 90% of companies say they prioritize diversity and inclusion in the workplace, only 4% consider disability in these efforts.

AIR’s data (from 2014) also showed that this wage gap has some serious consequences for the American economy. They estimate that if workers with disabilities received the same pay as their colleagues, they would add $141 billion to the economy (or 1% of the GDP). The country is also missing out on roughly $25 billion of tax revenue, and states could be bringing in $6.5 billion if the wage gap among the disabled was remediated.

Again, the wage gap hurts us all.

It may come as no surprise at this point, but women with disabilities are at a bigger disadvantage than their male counterparts. They’re about half as likely as disabled men to have jobs and work full-time.

LGBTQI+ persons

Due to discrimination, Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex employees don’t always identify their status at work, so it’s hard to get a grasp on precise wage gaps. The data we do have, however, reminds us that wage disparity is not just a gender or racial issue.

Often referred to simply as the “gay wage gap,” studies have shown that gay and bisexual men earned between 10% to 32% less than similarly qualified heterosexual men. Interestingly, lesbian and bisexual women tended to earn the same or sometimes more than heterosexual women. However, they still earned less than both heterosexual and gay men.

The National LGBTQ Task Force’s 2011 report “Injustice At Every Turn” has a wealth of data on transgender workers and their families, but their wage gap is even harder to measure since gender pay gap legislation requires employers to report on “men” and “women,” leaving no room for transitioning and gender non-conforming workers.

We know that there is a wage gap, as well as a significant increase in poverty levels among transgender individuals. But one telling statistic is that the earnings of male transgender workers slightly increased following their transition, whereas the wages of female transgender workers fell by nearly one-third. There have been multiple stories by transgender women attesting to the fact that they didn’t notice a significant gap in their wages or employment opportunities until they became women.

It should go without saying that sexual orientation and gender identity have no effect on job performance. Still, until Congress passes the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA), which would prohibit most employers in the United States from discriminating against workers based on sexual orientation or gender identity, we will likely continue to see these wage disparities.

Why do companies pay some people less, and what can we do about it?

[su_pullquote align=”right”]By attributing pay gaps to the choices individuals make and downplaying the role of discrimination, we willfully obscure the fact that they are persistent and universal.[/su_pullquote]Plenty of people have insisted that education, workforce experience, industry, occupation, seniority, salary expectations, family obligations, overtime, and full-time versus part-time work account for all wage gaps. But such arguments fail to account for discrimination, which plays a central role in equal pay.

By attributing pay gaps to the choices individuals make and downplaying the role of discrimination, we willfully obscure the fact that they are persistent and universal. And since some discrimination is the result of unconscious bias, trying to dismiss it as a reason for unequal pay robs us of the chance to understand the employee compensation system – and ourselves – better. The first step is to take a close look at where our economy provides unequal opportunities for people from education to training to career choices.

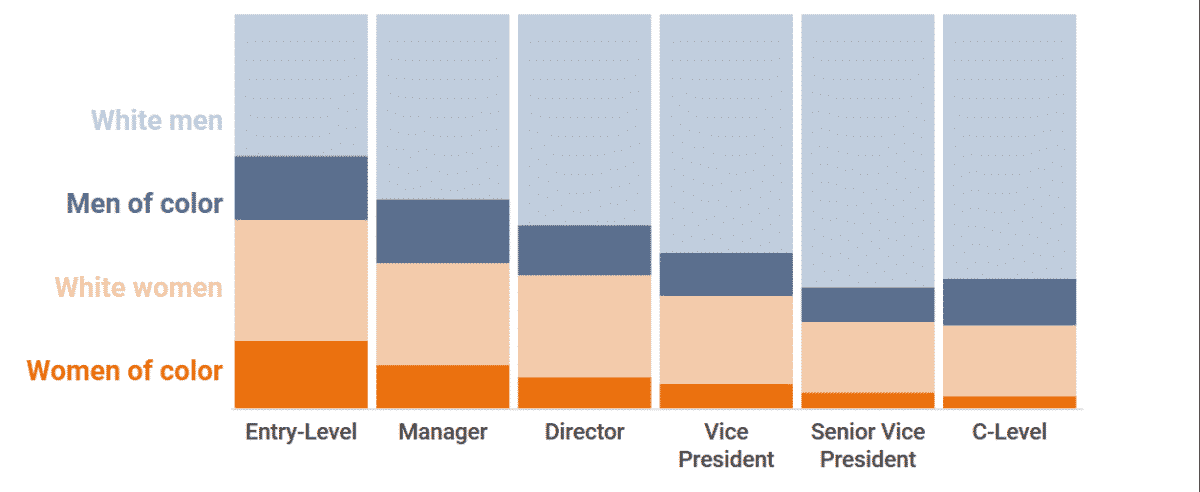

A person’s job choice is influenced by choices about educational paths, the presence of and advice of mentors, familial and societal expectations, the hiring practices of companies, and expectations about what their roles are outside of work. Women and minorities are at a disadvantage all along this path as they’re led into different types of roles based on societal expectations. We can’t underestimate just how much a lack of role models and mentors in a field or hostility in the college classroom plays a role in discouraging someone from entering it. And even if they do, the lack of diversity at the top levels of a company is discouraging – it’s a sign that no women or minorities have been promoted before them.

Take computer science, for example. It’s often listed as one of the highest-paying college majors, and at one time the number of women studying computer science was growing faster than the number of men. But with the rise of tech culture and personal computers (which was most often gifted to boys in their younger years), fewer girls were prepared to enter computer science classes in college because they didn’t grow up playing with the devices. When they do enter coursework or the major, they find a male-dominated and sometimes hostile environment that expects women to conform to male gender norms. The “bro culture” that developed in computer science made women the targets of sexual harassment and constant discrimination. And to top it off, they’re typically left out of social opportunities and even mentoring that can help them get ahead. That’s the kind of discrimination that leads to unequal pay.

Transparency is the key to equality

It’s important to note that closing the wage gap isn’t about paying people with fewer qualifications or fewer working hours the same salary as more qualified people. It’s about giving everyone the chance to earn the same wage regardless of their age, gender, ethnicity, disability status, sexual orientation, etc. To assume that those who want to close the wage gap want to give less qualified candidates the same wage is to build a straw man.

[su_pullquote align=”left”]It’s important to note that closing the wage gap isn’t about paying people with fewer qualifications or fewer working hours the same salary as more qualified people. It’s about giving everyone the chance to earn the same wage regardless of their age, gender, ethnicity, disability status, sexual orientation…[/su_pullquote]Giving women and other underpaid groups raises across the board simply because there is a wage gap would give rise to myriad problems. It might be prohibitively expensive for some companies or raise other legal liabilities. Raises across the board may reduce incentives and privilege underqualified workers, and may also signal to underperforming employees that their performance is adequate when it’s not.

But companies ought to look at their salary numbers and employee data, identify any unexplained wage gaps, and try to figure out how they came to be (for example: Are women hired with lower salaries? Are their raises smaller?). At that point, they can make an informed decision about closing and preventing wage gaps and eliminating discrimination.

With the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission announcing in 2019 that it would stop collecting pay data broken down by sex and race from larger employers; unfortunately, we’re moving farther away from that kind of useful data.

Conclusion

In the end, we all end up paying for the wage gap in one way or another. Driving families into poverty can help perpetuate a vicious cycle of underemployment and continued low wages.

As we’ve seen, the tax revenue and subsequent boost to the economy that would come with evening out wages for similarly qualified workers is measured in the billions of dollars. Closing the wage gap could be seen as a common good. After all, equal pay is the law in the U.S. for many underpaid groups.

But as long as we deny that a wage gap exists or obscure the information that would allow us to carefully identify their causes, we won’t get very far.

Further Reading:

The State of the Gender Pay Gap 2020 (Payscale, 2020)

The Simple Truth About The Gender Pay Gap: A 2020 Update (AAUW, 2020)

___

Visit our workplace diversity hub for further reading relating to current challenges faced by women and people of color, wage gaps, successful inclusion strategies, diversity in corporate and government leadership, effective talent acquisition and diversity programs, and how artificial intelligence affects diversity outcomes.

…a diversity score of 50.3% means that we barely see diversity in Congress at half the rate seen in our population. And this is our most diverse Congress ever!”[/mks_pullquote]While the number of women in Congress shows steady growth since 1980, our current gender diversity score for Congress is a measly 46.4% – a failing grade by any standard. People of color are doing better, but women of all ethnicities have made the least headway. Even as the most recent votes are tallied and we can celebrate the victories of our first two Muslim women, first two Native American women, first female senator from Tennessee and first two Latina representatives from Texas, white men still make up the vast majority of Congress.

…a diversity score of 50.3% means that we barely see diversity in Congress at half the rate seen in our population. And this is our most diverse Congress ever!”[/mks_pullquote]While the number of women in Congress shows steady growth since 1980, our current gender diversity score for Congress is a measly 46.4% – a failing grade by any standard. People of color are doing better, but women of all ethnicities have made the least headway. Even as the most recent votes are tallied and we can celebrate the victories of our first two Muslim women, first two Native American women, first female senator from Tennessee and first two Latina representatives from Texas, white men still make up the vast majority of Congress.